Kenema District lies within the Lassa fever zone. The seasonality of rainfall determines livelihood strategies, and relates to the ecology of the rodent carrying the Lassa virus as well as the virus’s transmission.

Land use is differentiated by age, gender, equity and wealth. Livelihoods in the rural areas include mining, hunting, farming (rice, tree crops, vegetable gardening), fishing, and commercial palm oil and biofuels production. In peri-urban locations livelihoods include service employment and trade. Different land-use changes may be increasing and decreasing Mastomys-human contact and virus transmission.

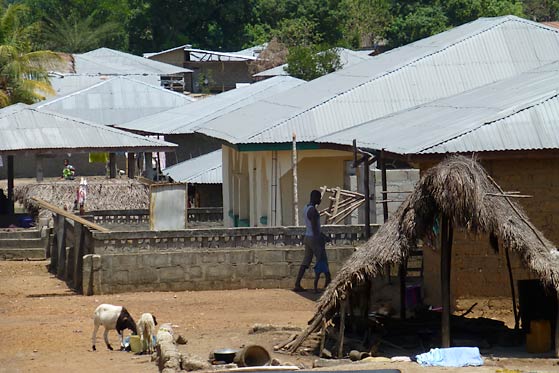

The settings for the Sierra Leone scenarios

This scenario envisages new roads, increasing population movements and continued urbanisation.

Mastomys might change to year-round breeding in urban and peri-urban areas, leading to increasing virus transmission.

There would also be an increase in mining, and agricultural commercialisation and intensification, e.g. palm oil and biofuels plantations. Wetlands would be drained, with some areas eliminated and put under plantation. In these areas, Lassa fever incidence would be reduced, due to a reduction in Mastomys from tree crops and industrial ploughing as well as fewer people as they move to urbanised areas.

The on-going smallholder commercialisation would intensify, shifting from upland farming to swamp use, enhancing Mastomys food sources, in turn increasing Lassa incidence in these areas.

Technological improvements in diagnosis would result in increased identification and recognition of Lassa fever elsewhere in Sierra Leone. However, this would not be due to a real increase in incidence, but an increase in detection and surveillance.

The interacting drivers in this scenario are:

This scenario envisages changing rainfall patterns and timings, with rain in the dry season and dry periods in the rainy season.

This could extend the breeding season of Mastomys, leading to an increase in Mastomys population and Lassa fever incidence in people. Intensification of year-round vegetable gardening and market crop production in swampy areas would further build up habitat and food sources that benefit Mastomys.

The changing rainfall patterns could mean people wait longer for their fields to dry before burning them, again leading to increased Mastomys populations. Current farming cycles and crops would prove impossible, resulting in growing poverty for smallholder farmers. A shift into cassava might, however, see a reduction in Mastomys.

Increased rural poverty would lead to increased vulnerability, malnutrition and reduced health-seeking behaviour, which may increase Lassa fever mortality. During seasons of food scarcity, increased competition between Mastomys and other rodent species such as Rattus rattus would lead to an increase in Lassa and other rodent-borne disease transmissions.

The interacting drivers in this scenario are:

This scenario envisages large-scale, foreign direct investment for palm oil production, biofuels and food crops for export.

This would come at the expense of local smallholder livelihoods, and especially that of women, who would lose cash income from their low-production farming.

Tree crop expansion in the uplands would, however, reduce Mastomys populations shifting from fields to forestation. Industrial ploughing of soil using tractors instead of hand tilling and burning of fields would reduce Mastomys habitat.

Growing privatisation of health care could increase attention on Lassa, but only for those who work on commercial farms. Inequality would increase, as well as food security for much of the population. A loss of material wellbeing and sustained social services would have the cumulative effect of more cases of human-to-human transmission within poorer households, increased human density in houses and reduced housing quality.

Land disputes would arise, burning of plantations and riots might result, and disaffection with government increase which would likely impact health-seeking behaviour.

The interacting drivers in this scenario are:

This scenario envisages people continuing to farm, but with an integrated approach to land management and human health.

The government would fund vaccines for rabies for cats and community-based approaches to encourage cat keeping in order to keep Mastomys numbers down.

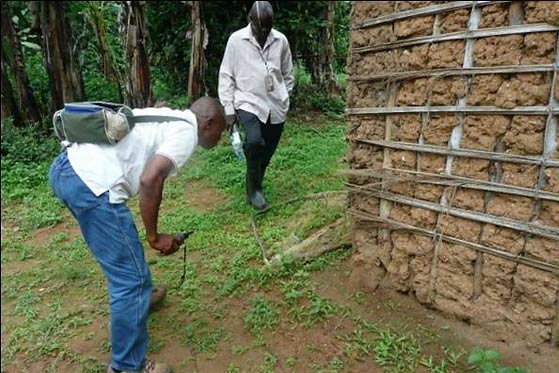

People would continue swamp farming, however this would be with an integrated pest-management (IPM) system in fields and in houses. An integrated management approach would be put in place for smallholders too, with the aim of maintaining traditional systems while trying to minimise the human-Mastomys interface.

Crop yield would increase from effective IPM and increases in income could be invested in improved housing quality, reducing Mastomys infestation in homes. Enforced housing standards would emphasise hygiene and pest management.

Savings groups, health groups, and others could be integrated into village One Health groups, with good knowledge and financial resources.

The interacting drivers in this scenario are:

The team in Sierra Leone identified two shocks.

First, a new Ebola outbreak, following on from 2014/15’s. This would produce benefits of increased diagnosis of Ebola, but could mean other diseases such as Lassa fever are overlooked in the short-term.

In the long-term, it could increase recognition of Lassa, which increased laboratory capacity across the country. A new, possibly completely privatised, health system could be built, and healthcare expand, along with the increased presence of NGOs with a disease focus.

Economic costs would be great though, with perhaps no growth for a long time. Mining companies could pull out, and the support they provided dry up. The World Bank and others might come in, possibly with a health focus.

Second, a new civil war. This could result in social collapse, more violence and increasingly authoritarian government. Boko Haram or ISIS could move in.

One surprise was identified, a major discovery of oil and oil price recovery. This would increase inequality in wealth and facilities. Infrastructure would improve, but only in Freetown, which would experience a high influx of foreigners and a construction boom. Elsewhere would be left to the mining companies.

Distrust and misunderstanding between groups, particularly between Freetown and the interior, would result, along with the potential for rebel groups to grow.

As Sierra Leone becomes richer it could become a market for vaccines. However, the focus would be on areas with higher economic impact. Most Lassa funding has so far been for diagnostics and vaccines from a military perspective, with little invested in prevention and control.

The team in Sierra Leone identified conflict and intensified agriculture as the major drivers within this system. They also added housing quality as an important driver for affecting Lassa fever disease risk. Move the cursor over each driver, and see how these interact. To compare with another country go to the interacting drivers page.

Thomas Winnebah, Njala University (country lead); Prof Andrew Cunningham, Institute of Zoology; Catherine Grant, IDS; Alie Kamara, Njala University; Morrison Lahai, Njala University; Prof Melissa Leach, IDS; Dr Lina Moses, Tulane University; Prof Ian Scoones, IDS; Dr Linda Waldman, IDS; Dr Annie Wilkinson, IDS.